Xeno Behind Stories

A Legacy of Passion Transcending Space and Time — Development Story of Xeno Series Trumpets

Chapter Two: Departure from the Schilke Ideal

In 1977, Yamaha opened its first wind instrument shop, Atelier Tokyo, in Ginza, a hub of musical performance. Kawasaki, who had returned to Japan after training at Schilke Music Products in the US for two years, was named the atelier’s first chief manager.

Hiroo Okabe

While Kawasaki was busy catering to the needs of players in Japan and abroad at the atelier, Hiroo Okabe, who joined Yamaha in 1974 and would later become Director and Managing Executive Officer, was involved in design at the Yamaha HQ. Okabe, who was placed in charge of trumpet design during his fourth year at Yamaha, had been a long-established brand's trumpet devotee since his time in university and wanted to create musical instruments which would be as widely loved by players as the long-established brand's instruments were.

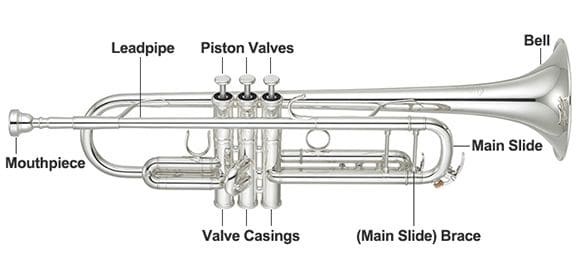

This brand is a US-based manufacturer of high-quality trumpets and the choice of many top artists. Its basic construction of trumpets differed in almost every way from the Schilke trumpets Yamaha had been basing their designs on, from the thickness of the brass and length of the leadpipe to the presence of a brace on the main slide. In fact, Schilke’s discontent with the trumpets being sold at the time, including those from the brand, is what led him to start his own company. It only made sense that ideals would differ between the brand and Schilke.

Structure of the trumpet

When the still new Okabe was placed in charge of a model redesign which had been in the works since the time of his initial placement, he proposed extensive structural changes following thorough research into the well-established instruments. For example, Schilke emphasized pitch above all else, which is why Yamaha products had not utilized braces up until then, but Okabe suggested adding them. "Back then, more than accuracy of pitch, players were drawn to the indescribably beautiful timbre of this brand's products, and they wanted musical instruments they could feel confident relying on. In that case, we needed to show them we understood their needs by creating the kind of products they wanted," said Okabe, explaining his line of thinking at the time.

Okabe was attempting to depart from the Schilke ideal which Yamaha had preserved so diligently, while Kawasaki had learned all he knew about trumpet design from Schilke himself. It was inevitable that the two would clash. However, Kawasaki had heard direct feedback which occasionally included severe criticism from players at the atelier and gradually began to accept Okabe’s ideas as he came to understand that many players did indeed want instruments more similar to that brand's products. Although it felt like a betrayal of Schilke, they knew they would need to listen to the players in order to take Yamaha trumpets to the next level. Kawasaki felt this to be truer with each passing day.

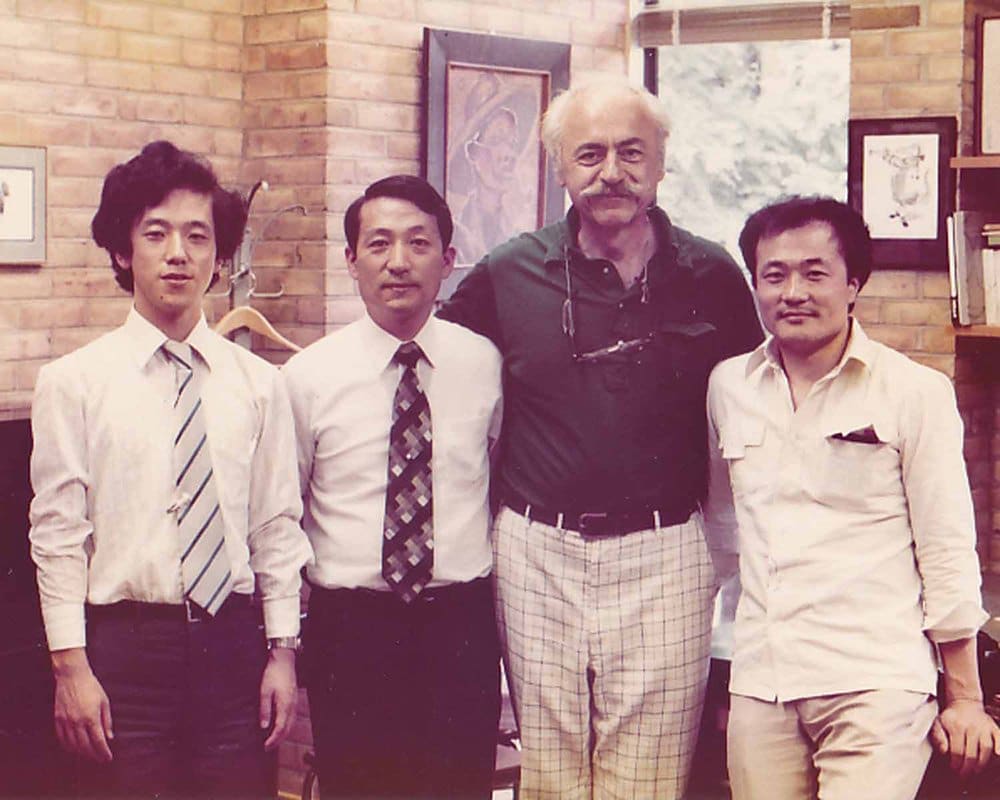

In 1980, the first "post-Schilke type" prototype was completed, and Kawasaki and Okabe headed to the US to have it assessed by artists there. The prototype was highly praised by the artists, who were happy to see the new direction Yamaha was taking.

Kawasaki attempted to inform Schilke of the development of the post-Schilke type models several times, but due to Schilke being injured and other unforeseen circumstances, the timing never worked out and Kawasaki never actually got to tell him. However, it is likely that Schilke heard the news from one of the American artists who tested the prototype, such as Adolph Herseth, principal trumpet of The Chicago Symphony Orchestra, or Armando Ghitalla, principal trumpet of The Boston Symphony Orchestra. From time to time, Schilke would tell Kawasaki and Okabe, "Don’t go backward." Hidden within this message was a play on words warning them not to become another old firm.

Hiroaki Imaoka

Forced to use a wheelchair in his final years, Schilke still continued to visit Japan and offer his guidance until 1981, one year before he passed away. He likely felt conflicted internally about Yamaha’s new direction, which departed from his own ideal, as evidenced by occasional friction with a young Okabe, whose devotion to the other instrument was clear. However, despite Schilke’s dominating presence at Yamaha, Okabe held strong to own his convictions and was never afraid to express his ideas. Hiroaki Imaoka, who witnessed the interactions of these two men firsthand, insists that "even if the direction of their courses differed, they both shared the same goal of forging ahead toward new heights." Imaoka remains confident that the evolution of Yamaha trumpets was supported by the passion of both men.

In 1982, the new post-Schilke type Custom trumpets were released. In addition to the adoption of a "one piece bell*1", all of the new models featured design changes to key components which addressed long-standing issues and vastly improved overall quality.

After graduating from a music college, Imaoka began working at Yamaha and joined the design section in 1980, which means that he shared responsibility with Okabe for the company’s first major trumpet model redesign. "The most characteristic feature of the post-Schilke type models was the addition of a single brace," he explained. This brace gave the instruments the mellow and clear sound demanded by many. "Up until that point, even if players chose a Yamaha for their first instrument, they often decided to purchase another brand once they had improved, but I think that slowly began to change with the introduction of the new models," Imaoka continued.