Q&A with John Oestmann, the composer of Rooftop Renegade

ROOFTOP RENEGADE

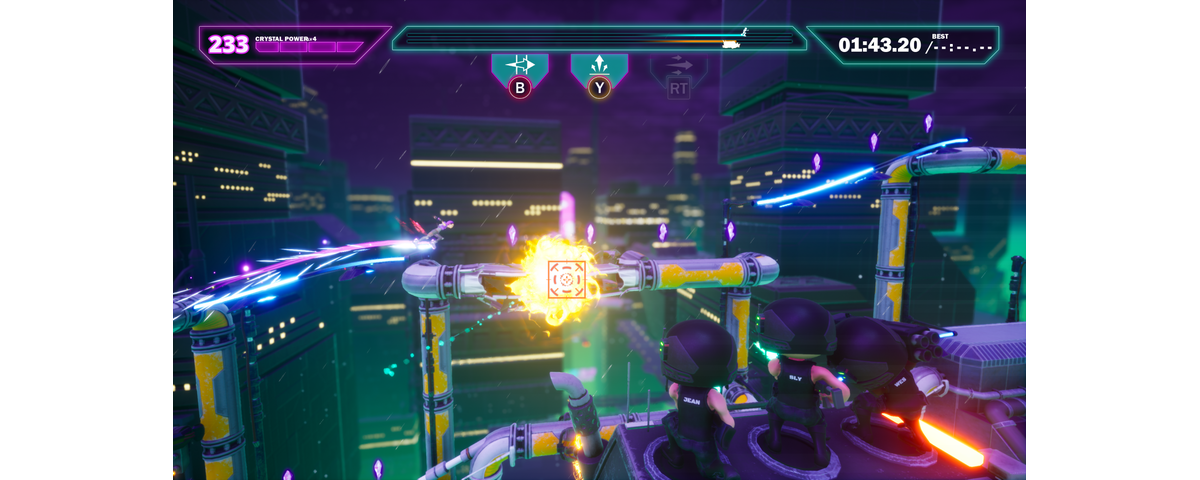

Rooftop Renegade is an Indie video game developed by the Adelaide based indie game studio Melonhead games. Rooftop Renegade was one of the 6 Australian Indie games appear at PAX 2022 as winners of the Indie Showcase.

The game is a fast-paced Sci-Fi action platformer that’s tells the story of Svetlana, a hover blading outlaw with the ability to portal through time.

Take on the evil Globacorp by stealing scattered time crystals before they catch you.

BOOST, GRIND and WARP your way through challenge levels, generated levels, and chaotic local multiplayer, all while Globacorp’s attack squad chase you down!

YAMAHA AT PAX

Interview conducted by Boyd Gill -Home Audio Product Manager, Yamaha Music Australia.

At this year’s PAX Melbourne convention, we knew we needed an amazing game to use in conjunction with our own hardware that will be on show and importantly, we wanted it to be one of the incredible games made within our talented indie scene - and Rooftop Renegade was a perfect candidate. Created by Adelaide’s Melonhead Games, not only is Rooftop Renegade a fun looking, simple to learn, difficult to master platformer but it also has a particular emphasis on using sound as part of its driving force and game play taking advantage of newer developments in what’s called Reactive Audio. Not only were Melonhead Games kind enough to come on board and allow us to display the unreleased Rooftop Renegade on our display at PAX, but they also put us in contact with their sound composer John Oestmann.

What follows is an interview I conducted with John via email prior to PAX. We dive into some really interesting topics about how game audio design works, the unique challenges it presents as an interactive medium and also, we take a turn into the virtues of using newer song writing toolsets and techniques completely comprising of a digital workspace and fully digital instruments. I hope you find it as fascinating as I did and the next time you jump into your favourite game, you spend a little extra time just listening to it and taking in all the incredible work that’s gone into crafting the soundscapes that make that world real and exciting.

THE INTERVIEW

First, please introduce yourself and provide a little background in terms of experience and educations that has got you though to your current career, are you a career musician who found your way into game score composing or did you decide you wanted to be a game score composer and focused on that specific craft? How would you describe your music to those who have not heard it?

I'm a composer for video games as well as producing my own music under the project "Soundworlds." I grew up playing video games, and just like so many others of my generation, I always wanted to recreate that magic.

Over years of trying and failing to create whole games myself (as I know many others have also experienced), I gradually realised that it would be more effective to focus my efforts on one area. I asked myself if I had to pick one area of games to limit myself to, what would it be - and realized that was music.

I was self-taught and had already been making music for about 8 years, but around this time I decided to take composition more seriously and ended up going to the University of Adelaide here in South Australia. Without going into the convoluted details, I unfortunately had to drop out after 6 months. Though as luck would have it, the career decisions I made over the next couple years ended up bringing me to a share working office where I was working alongside concept artists heading into the video game and film industries.

At the time, a small business I had started wasn't really working out, and so I realized that if I was going to have a chance to work in the video game industry, this would be the time and place to do it.

I started focusing on developing my skills in the craft again, learning reactive audio with FMOD and building up my portfolio. Fortunately, by the time I met the guys from Melonhead Games at a local networking event, they were after a composer for Rooftop Renegade and I could share both my portfolio and insight into how reactive audio might benefit them. They thought my style was a good fit for the project, we happened to just get along well, and the rest is history!

Stylistically, my music always tries to convey a scene or location. Growing up with Koji Kondo's music to games like Zelda: Majora's Mask and Star Fox 64, the link between music and the location it is trying to express became very much ingrained in me. To this day I think it has influenced how I listen to and interpret music, as well as my goals with composition - both in and out of video games.

Over the last few years, I've also consciously started to focus on electronic-based music rather than classical orchestration. While I enjoy both styles, there appears to be no shortage of classical orchestrated music in film and games, and so developing myself in an electronic direction is one way I can (hopefully) differentiate my music.

With video games being such an interactive story medium, what do you need to take into consideration as you build a games soundtrack, and how might that vary from what you know about creating audio for a film?

While I haven't worked on any large films, I have watched many interviews with film composers over the years and tried to analyse certain film soundtracks. There are a lot of similarities between film and games, but also some key differences.

A movie, just like a song you'd listen to on a streaming service, has a start and finish and moves in one direction. It plays exactly the same every time you listen to it. With games, you have the opportunity to make the music (or sound effects) reactive: changing how it sounds or where the composition heads based on what the player is doing. Neither of these approaches are inherently good or bad, but they bring their own limitations and opportunities.

One powerful technique you can use in music is called a "motif" - essentially a melody that is tied to a character, or place, or story object. For the sake of example, let's go with a character.

Every time that character comes into the scene, you would play that melody, or a variation of that melody. Each time you do this, it can strengthen the emotional reaction to that melody and to that character. If you then have two characters fall in love and kiss at the end of a movie, you might want to play both of their motifs at the same time, as this will give you the emotional gut punch of their motifs fusing together.

In a movie you know exactly when characters will be coming on screen and so you can compose the soundtrack accordingly. Both the film and the soundtrack can polish that emotional trajectory knowing exactly where everything occurs in that timespan. It is a single timeline.

The difference in games is that you can implement the soundtrack to evolve in any one of countless ways (or timelines), and you need to be mindful of how different players might experience it. For example, depending on how the player is doing, Section 1 of a track might loop. If they start playing better, it might switch to Section 2. Even better, then they get Section 3. But if you've only put the motif in Section 3, then an inexperienced player might never get to hear it. They would walk away thinking that the music for this level is only composed of Section 1 and 2, and they never hear that key emotional part of the music. But this could also be a good thing by design - rewarding experienced players with the "best" music.

As you can see, once you make music reactive in games, the amount of possible listening experiences the audience can have increases exponentially. This can be very effective, but it just means you need to be mindful of designing your system of music to work effectively for different players and playthroughs.

So reactive audio sounds like a huge part of the interactive experience a player can have while making their way through a video game that just cannot be accomplished in a movie of TV show because like you said it’s a linear telling of the storey that the viewer has no actual interaction with, could you please provide a few more examples of how reactive audio might be used with in a video game? Is it just something a simple as the music track changing, or even just the tempo ala Mario becoming invincible from a Super Star or can there be more to it? What are some of your favourite examples of reactive audio you have come across?

Reactive audio in games can be used in countless ways, and as it's all fairly new, we're only just scratching the surface. Originally reactive audio meant playing sound effects at certain times, or cross-fading between two different tracks of music (e.g. Mario's invincibility theme when he gets a star). More recently, Middleware like FMOD or Wwise has made it a lot more accessible to implement layers of music or sound effects that can play in different patterns, with different intensities, or different audio effects applied to them based on what the player is doing (take a look at Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice for a really powerful example of this).

We're now entering an era where sound and music can be synthesized live by the game (while not the only example, from what I've seen of Unreal Engine's Metasounds, it looks like they're starting to build a toolset for this).

In theory, this means no pre-recorded material - no samples - every part of the sound and music design can be generated live. All of these pathways have a ridiculous amount left to explore.

Purely speculative, but I wonder if we will start to see standardized theories of non-linear composition for interactive media being taught in schools and universities. I know classical music has been exploring non-linearity for a long time, but the specific case of non-linearity in games is a very tangible case that most gamers now have experienced first-hand.

One caveat I would like to add to this though: for all of the excitement around what reactive audio can do, I've personally found that as you increase the scope of possible pathways for the music, it makes it harder to make a solidly good piece of music. It can definitely be done, but it starts to require an exponential amount of work to cover off all possible pathways. I am not sure if all game designers agree with this, but I do believe that players have a more powerful experience when the soundtrack is static, but really good, as opposed to when it is very reactive, but never sounds that great.

Please take me through your process a little if you’d be so kind, what are the broad strokes of constructing a games soundtrack? Do you start by working with the programmers and producers at an early stage or do you have to wait for a mostly finished game?

I know in film production this can vary greatly, sometimes the composer will come in while the film is shooting and provide temp scores and mood to help the actors, sometimes they won’t start work until the film is compete and they can follow the story beats. How does this work for a video game, at least in your experience?

This really depends on the project and when I'm brought on board. With Rooftop Renegade, the team already had the game functional and playable, with the first two worlds implemented. This meant I could basically use their story and visuals as a reference point and try to channel that through the music. I am currently working with Paper Cactus Games on a game called Fox and Shadow, and I have joined the team much earlier in the production process.

With this project, we are finding the artists, narrative writers, game designers, and myself in audio are all inspired by each other's work, and so you have more of a cross-pollination parallel development going on.

Having said that, in all cases, there is a lot of discussion, feedback and iteration with the team. Through ongoing discussions I really try to work out what kind of emotional experience the designers are trying to create and use that as my key point of reference when designing the music. This generally helps us all move in a similar direction, though you have to be aware there will always be discussion, feedback and iteration. That's not a bad thing, it's just the nature of working on a team building a coherent and focused work together.

How did you get involved in Rooftop Renegade? Did it present any unique challenges compared to other projects you have worked on? How long did it take from start to finish to complete the soundscape on your part?

As described in my first answer, getting involved in Rooftop Renegade was a genuine mix of focused work, skill-building, keeping aware of opportunities around me - and biggest of all - being lucky to be in the right place and right time. Rooftop was the first major game project that I had worked on, so while it's tricky to compare it to other experiences, it might be worth mentioning some key things I learned that have helped me on projects since.

Developing the skill of taking aboard good feedback, discussing well and iterating on the work is a key one. I have heard other composers say "you just have to do what the boss says." This obviously depends on what the project hierarchy is, but I feel pretty passionately against that mindset. The discussions you have with the team are two-way. This means that if you present an idea you legitimately believe will end up in a better product, you should explain why you believe that.

As the composer, you have (hopefully) thought the deepest about how the music works within the game, and so it is worth taking your own specialist opinion seriously. By that same token, if other team members can give a constructive reason why they believe something should be changed, it is worth considering that feedback seriously. I have to be honest and admit there were plenty of times where I presented a potential track concept and the others disagreed that it evoked the world it was made for. Coming back to it a couple days later, I completely agreed! One thing I have found helps combat this "ego" side of things is to keep my own personal music releases going as well. Having full creative control over my own music meant I could let the games' music be more consistent with the game, rather than just whatever I was personally passionate about at the time.

It wasn't full time work and workload intensity changed over time, so it's hard to put a timeframe on the full music development, but I was actively working on the project for about 2 years.

When writing the music for the game, does the gameplay influence the music and mood or does your own musical tastes influence the composition because that’s what you want to hear against the game play?

My personal taste definitely comes into play, and I will push an idea if I am into making that style - but only if I genuinely believe that the style can work well within that game. The actual gameplay-music-system often has a large impact on style of music too. For example, If we know that the music will be made of short loops that change based on player action, EDM, Hip Hop, Ambient or Minimalist Classical can all work quite well as it won't end up sounding too different to a regular song you would listen to in those styles.

How conscious are you of the player when creating a game soundtrack are you working more to enhance the actions portrayed on screen or make the player feel an emotion or deeper connection to the game?

I think I kind of subconsciously imagine myself as the player while I’m composing it - probably as most of my inspirations growing up are experiences of being the player. I also aim to design the music in a way that players can enjoy listening to separately after playing the game (e.g. on the Soundtrack Release). Though the clearest insight into player experience always comes from playtesting - both ourselves and with play testers. Often audio works great in theory, or as individual music or sound effects files, but when you see someone smashing through a level and all of the audio playing at the same time, that’s when you realize how much you need to rebalance things for a better player experience!

Where do you find the inspiration for your compositions, by which I mean do you need to sit down and just tinker with a track piece by piece maybe like a song writer would with a guitar? Or do you find once you get started it all just flows together.

As much as I’m always trying to nail down a process that “works every time”, my process generally changes most of the time. Though over the years, I’ve found two things: 1) exploration and experimentation keep things enjoyable for me, and 2) If I build up a loop that expresses the core idea, it is usually then a process of iteration / layering / transforming from there to get to the final product. Sometimes it flows, and sometimes you hit that classic brick wall of frustration and the self-doubt begins. But I think once I realized that it is always a process of building up the piece through small iterations, that helped take away a lot of the pressure. Unfortunately, I am not one of those mythical composers who can imagine the whole piece in my head first. For me it is always the sum of many small incremental ideas and changes.

In the early days of video game composing, the resources to create and store music files were extremely limited, today many of your compositions both in games and more so within your own creative projects still use many of these techniques to create the music. Other than the fact that this type of music brings back wonderfully nostalgic memories for those us who grew up playing video games during these early time period, what is it you love about creating music using digital instruments and samples. Some might see the reduced number of channels/sounds available as a limitation but how do you see it as a unique way to create and to still be able to remain sounding dynamic and to convey a sense of emotion and connection to that world or storey being presented?

I have a lot of respect for the compositions of 80s and 90s games for that whole reason of creativity through limitation. The original Game Boy could only play 3 tonal waveforms and 1 noise channel at once, and yet so many iconic game themes were born in this era. The very limited sound palette and simultaneous voices forced composers to utilise strong melodies and harmonies to convey the emotion they were after. Now that we have near unlimited instrumentation, I suspect it can actually dilute a composer’s energy, spread thin across melody, harmony, orchestration, sound design, mixing, mastering, implementation, etc.

For clarification, it hasn’t always been appropriate in the games I’ve worked on to take such a minimalist approach. Funnily enough, if you listen to "Chronos" from Rooftop Renegade you can hear many instrumental layers coming in and out, and yet I would say it is the most "minimal" track on the soundtrack. Most games I work on do require a more "modern" layered soundtrack, though I think the key piece of wisdom we can take from the early days is that a solid melody or harmony can transcend the aesthetic of whichever era you are composing in.

In my own music, these retro inspirations are more direct. For the first two albums of the Soundworlds project, I was using virtualized versions of synthesizers that were very popular in the late 90s / early 2000s to try and capture that era's sound. The current album I am working on in Soundworlds utilizes a combination of a limited number of instruments as well as Sample and Bit reduction to capture the aesthetic of the Game Boy Advance specifically. One of the benefits of these current creative limitations is that they've allowed me to use my energy to explore and get creative with sound design and synthesis at a much more fundamental level.

When deciding on the performance of a soundtrack mix, how are you testing it, especially when combined with the game play? Do you run it through Studio Monitors or headphones, multi-channel sound system? How do you test it so can get an idea of how the players might experience it across the various sound solutions they might be using to play the finished game?

You've actually hit on a really important point. I use headphones while composing and testing, but later in the process it is very important to test on a range of devices to try and simulate the different platforms players might be hearing the soundtrack or sound effects on. Smaller platforms (like a phone, laptop or undocked Nintendo Switch) generally can't reproduce low frequencies well, and so a track with a lot of high-frequency content can sound top-heavy, or at worst, piercing and grating. Everyone has their different ways of testing, but I generally listen on my own headphones, on my phone, and then in my car sound system with the "double bass" setting cranked up. While it might not sound perfect on all 3, if there are any major concerns that will come out, I've usually caught them by the end of those tests!

One more key part of this is through playtesting. There was a point working on Rooftop Renegade where we realised that all of the sounds and music sounded good in isolation, but as it is a very fast-paced game it ended up with too many sound effects happening at once and drowning out each other. It was only after seeing this through playtesting that we realised we had to shorten and tighten everything up.

Do you have a favourite game soundtrack or theme?

There are a number of soundtracks that I really love, but one that continuously inspires me is the Machinarium soundtrack by Tomáš Dvořák. At first playthrough, it just sounds great and hits certain emotional story beats really effectively. And now, each time I listen I find more layers of subtle, yet rich sound detail he’s woven in.

Do you have any equipment you are especially fond of?

Nothing specific. I am generally more interested in virtual instruments and how far they can go. So in that case, I suppose my computer!

In terms of using digital / virtual instruments, as someone who’s played a handful of instruments over the years, some more successfully than others I’d be curious to know are some digital/virtual instruments harder to master than others, even though they are digital representations of an instruments do they still have their own limitations and intricacies to play in the context of creating a music track?

This really depends on how a virtual instrument is being played. You can control most virtual instruments with a MIDI Keyboard attached to your computer, and so you can play them live if you feel comfortable on the keyboard. Some composers / producers actually aren't that great at playing real instruments, but they get really good at drawing the MIDI notes into the DAW to control that virtual instrument. Other producers might work mostly with pre-recorded samples they've downloaded and get really good at manipulating those.

Since as far back as machines have been able to make music (looking at you, Phonograph), people have argued that their music has always been inferior to "real music" played live, by people, on real instruments. While it is true that people playing real instruments have mastered a much deeper level of nuance and expressiveness historically, I think the argument that electronic music should try and sound like "real music" was broken from the start. I grew up with the half-real-half-synthetic sounds of the 90s synthesizers, and so much of the music that really moves me is built from those not-quite-real sounds. The difference is that today with MPE and MIDI 2.0 starting to gain adoption, the level of nuance you can generate with MIDI-controlled virtual instruments has exploded as well.

It is also worth noting that I've heard some vocal teachers say they've noticed the way people sing change now that they're constantly exposed to pitch-corrected singing in pop music. Not only are there these all different ways of making music legitimate, but we have this really interesting cross-pollination happening now too.

What’s the one thing you’d like someone to know about creating a video games soundscape?

Don’t be disheartened if you don’t see/hear your style of music in video games. Your style isn’t “wrong,” and in fact it’s probably a great opportunity for a game to showcase a new type of soundtrack.

Do you have any other projects you’d like to readers to check out? I know you’ve converted your Twitter feed into a pretty interesting concept for presenting your work in a unique way. What is Soundworlds datapedia all about?

Readers can definitely check out:

Rooftop Renegade here and join the mailing list or wishlist:

https://rooftoprenegade.com/

Fox and Shadow development can be followed here:

https://www.papercactusgames.com

Soundworlds Datapedia is an ongoing musical project of mine where each track is a different location in the same Soundworlds Universe. Listeners who enjoy the music can read the lore entries to gradually explore the Soundworlds Universe itself.

Collections of the Soundworlds music is also released as albums on streaming services for easy listening. The whole project is the culmination of years of experimenting with ways of keeping music ingrained in a "world" you can explore, without it specifically being in a video game.

The good news is that if that does interest you, this is planned to continue as an ongoing project with the Soundworlds Universe growing larger and deeper over time.

Keep up with John

Follow John and his Soundworlds Datapedia project on Twitter

@john_oestmann

Or visit his website:

https://www.soundworlds.com.au/